March 2013

CORA COHEN The Responsibility of Forms

by Nora Griffin

Guided By Invoices

February 15 - March 16, 2013

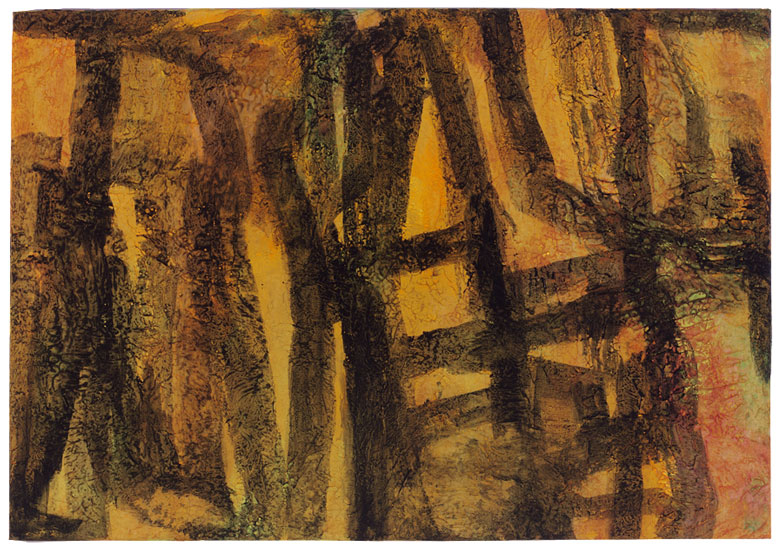

Drawing5 Yellow, 2013, 37 x 53", acrylic mediums, Flashe, pigment, watercolor on linen

“Classical language … establishes a universe in which men are not alone, where words never have the terrible weight of things, where speech is always a meeting with the others.”

—Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero

Language is integral to painting’s structure. Of all the art forms, painting is at once the most archaic and the most supremely socialized—it comes to us through centuries of babbling dialogue, entrenched in history and myth, and resplendent with references to other paintings and the civilizations that grew around them. Cora Cohen’s paintings (all 2013) could be described as “classical” in their presupposition of an active viewership, ready to take up its end of the conversation. Her art is not explicitly about language or readable as a text, but her choice of forms, colors, and supports are remarkably fluent in their own vocabulary. The paintings are staunchly abstract with no direct reference to landscape, the body, or art history, and appear simply made, on the verge of a modesty that belies their medium to large format (the largest measures 69 by 91 inches). Cohen’s mixing of graphite powder, acrylic, watercolor, ground pigment, and gesso lateralizes the traditional hierarchy between “painting” and “drawing,” and loosely connects her work to the artists associated with the post-war European movement of Art Informel. A negative comment made to the artist in the 1970s, “your paintings are like large drawings,” has indeed stayed with Cohen as a worthy course to pursue.

Cohen’s paintings can be considered linguistic in their insistence on the value of approximation. This is most apparent in a color palette that cannot be labeled artificial or natural, but instead suggests what might be found at the back of one’s mind. Her work shares with other successful abstract painting a preoccupation with translating subjective, temporal experiences that defy quick interpretation. The darkening light that bridges 4 and 5 pm has its visual counterpart in a painting such as “Curtain8 Black” that seems to tonally fluctuate the longer the eye rests on it. The muted vibrancy of “Curtain7”(discreetly installed in a back room off the main gallery) and “Drawing5 Yellow,” evoke the naturally occurring psychedelia of an iridescent puddle. It is often difficult to differentiate between pigment and texture, as Cohen’s paintings are composed of thin washes of color fused with a reptilian under-layer of acrylic medium. The color appears oxidized to its most elemental characteristics: carbon gray, sulfur yellow, and rust red, with specks of blue and silver if you gaze long enough. The surface is a continuous skin and the paint is like smoke on a window, registered and disappearing at the same moment. A good definition of abstract painting could be found here: a meeting between the skin’s pulse and the glassy coolness of a mirror.

Cohen’s recurring use of the word “Curtain” in her titles suggests an upfront approach to painting as a window onto illusion. A curtain has two roles—as a decorative or functional household item, and as the heavy fabric that separates a theatrical or cinematic event from an attentive audience. The dual meaning reinforces how an artwork may be seen as both profanely pedestrian or as a sacred portal. In “Drawing4 Grey” and “Small Drawing,” Cohen further plays with the concept of the curtain with small, unpainted openings in the paintings’ surfaces that function as a peephole to nowhere. These small ellipses humanize, ever so subtly, the work for our eye. The choice of a narrow stretcher bar frame also adds primacy to the surface’s illusion. The one exception is the aptly titled “Little Nomad2,” the most object-like of the group, rough around the edges, with an oval-shaped scrap of wood veneer adhered to the linen’s glistening and dirty face.

A painter’s attention to surface can be named (and hence forgotten) with a host of adjectives: rough, smooth, slick, porous, intricate, dense, clean, etc. But how does one describe the indeterminate surface that seems to give out more information the longer you look at it? Cohen’s art practice gently schools your eye; it asks that you look for the words, or the memory, that most closely aligns itself to the work in question. The youthful figure of the art student is one that kept returning to me as I stayed in front of her work. “Drawing4 Grey” and “Small Drawing”have the cursory quality of a charcoal sketch, discarded on the floor after a life-drawing class. Drawing is abstracted to its essence, a rubbed graphite blur, taut with the energy of observation and evaluation. If we needed to find a representational image associated with Cohen’s painting, it would be the image of writing. The crisscrossing, limb-like forms of “Drawing5 Yellow” and “Red Tablet” convey an alien calligraphy dilated in water. Cohen’s preference for mixing wet and dry media contributes to a sensation that is at once lush and arid, and her surfaces manifest a strange combination of hurried gesture and slow build-up, as if painting alla prima, literally “painting at first attempt,” was practiced over and over, until a form coalesces on its own terms.

Cora Cohen’s painting requires a reader’s concentration, one that mimics the opening and closing of a book, when in a flash of consciousness you turn away from the page to look into space. In a minute, or perhaps even longer, you may turn back to the artwork with new awareness. Criticism also has the power to turn one’s concentration back to the enigma of the artwork in question, but this form of art writing is a rarity in publications which prize verbosity and redundant historicizing over immanent articulation. In a contemporary art world blinded by what is not art (the market, social media, lifestyle), where everyone speaks yet few say anything, we easily forget that it is the responsibility of singular artworks to re-focus concentration and suggest new modes of seeing. The work can look back at us, and if we search we may find the right words to describe that encounter.